Playing our way to conservation? Experimental games in the Andean countryside

Experimental games, or field experiments, are a common tool deployed by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and economists to measure…

Experimental games, or field experiments, are a common tool deployed by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and economists to measure when, why, and how people make different kinds of choices. This data, in turn, is used to inform public policy and generate development projects. In 2016 Adam ran a series of experimental games with Andean farmers for the NGO Bioversity International to understand what kinds of incentives farmers would need to conserve threatened varieties of quinoa.In this piece we reflect on using experimental economics, or framed field experiments, as a way to understand human behavior and choices. Adam Gamwell and Corinna Howland produced a podcast and a transcript for this story.

Check out the episode here, hosted by our friends at This Anthro Life: Food Futures Podcast Episode 1: Playing our Way to Conservation

(Also available on iTunes and SoundCloud)

Here are some excerpts from the interview:

Corinna: Adam, why don’t you begin by walking me through a typical game day.

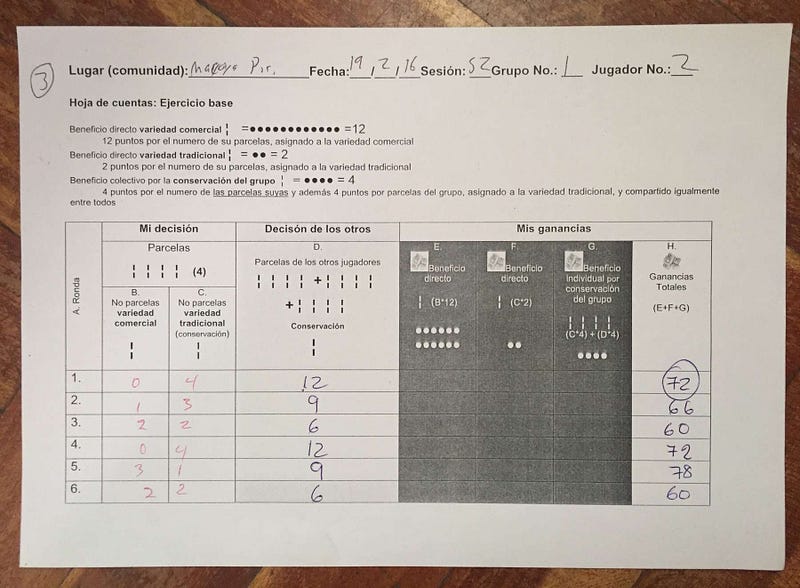

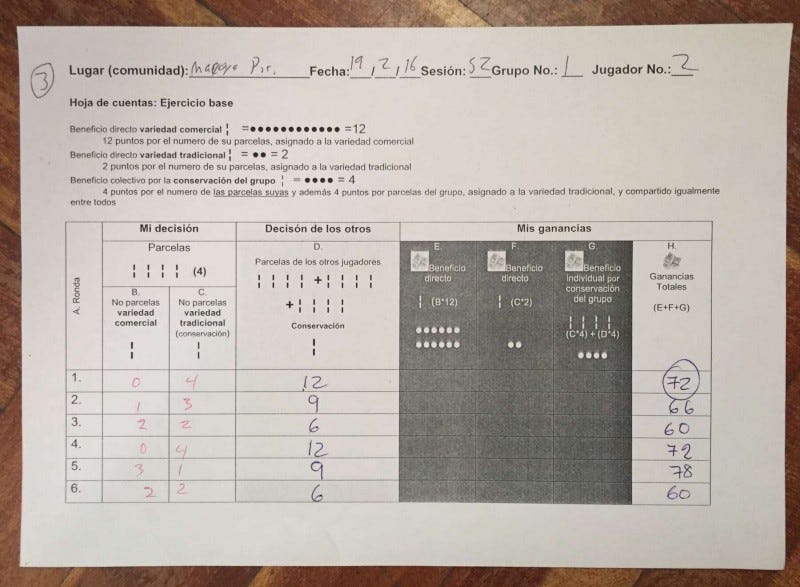

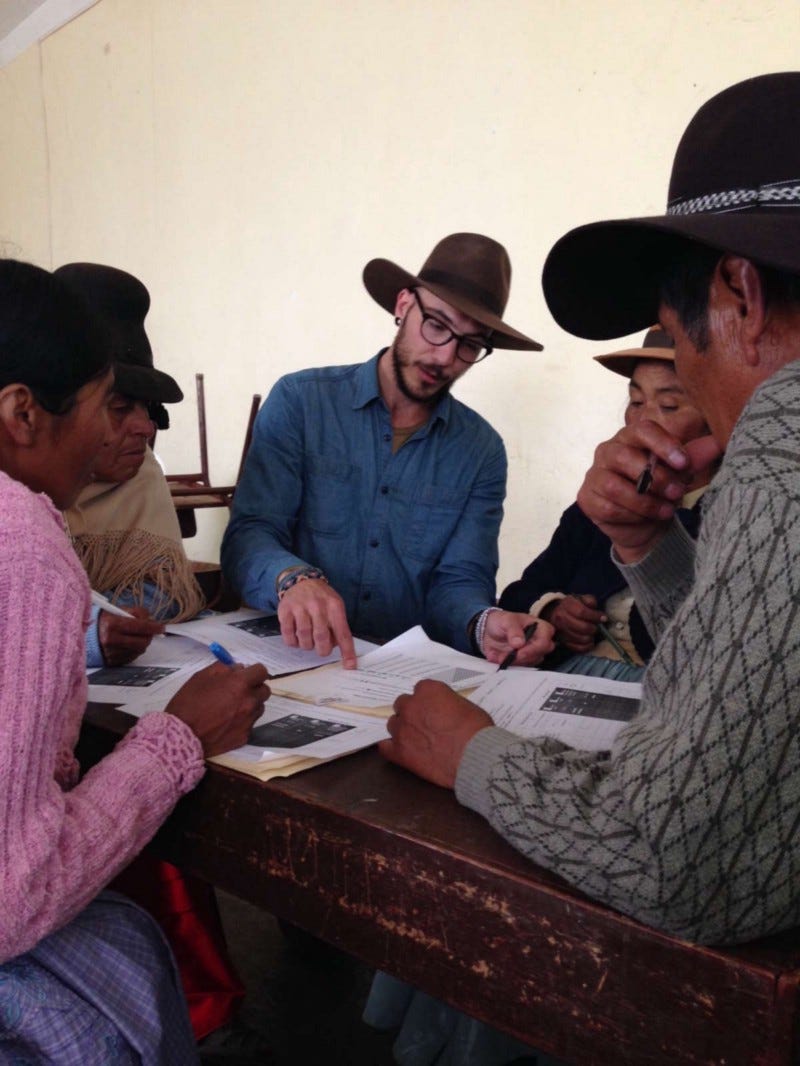

Adam: After an hour and a half of driving along a highway then onto a dusty road, we find ourselves in a classroom that we’ve borrowed from a community. My team consists of an economist, an agricultural engineer, and two agricultural scientists. We stand around for about an hour waiting for the farmers to turn up, and slowly they shuffle into the small classroom, looking warily at the hand-drawn posters that we’ve put up on the walls, explaining how to play the games. Once our group is in the room, we split them into teams of four — we normally played with between 12–20 people. Each person has a folder in front of them which contains their game sheet, where they fill out their choices. Then based on their choices and the choices of their group members, they earn a certain number of points. The game is based on the cultivation of two different kinds of quinoa — commercial varieties that you can buy at a supermarket; and traditional varieties that don’t have any market value, but do have other kinds of values — they’re more adaptable to climate change, they’re more resistant to drought and pests.

C: What was the scale of the project?

A: These games ran from February 9th to March 10th this year, about a month. And we visited 15 communities overall, so it was a very long month. Each game took about 4 hours to play, which of course didn’t include how much time we had to drive between each place.

C: Because you were going to communities all over the Puno region?

A: That’s right. We tried to split the games evenly between Quechua and Aymara ethnic groups, as one variable to measure.

C: So how did people actually play the games?

A: Great question. There were between 12–20 participants in each community, and we put them into groups of 4. We played a total of 18 rounds, split into 3 chunks. Each player had 4 units of land per round, and they could choose to plant either commercial or traditional varieties. And the difference of why they would choose these is based on the amount of points they could earn. While the commercial varieties had a higher point value for an individual player — if I grew commercial quinoa I would earn more points for myself — the traditional varieties had a group value also. So they had lower individual points, but the idea was that there was this public benefit to growing traditional quinoa. After each round, their points were calculated based on the choices they’d made — how much land they’d set aside for commercial or traditional quinoa. And then these points were tallied up alongside those of the rest of their group, to find out how much they’d conserved.

C: So the choices that other people in the group made also had an effect on each individual’s outcomes?

A: Exactly. This is based on the idea that conservation is a collective activity. Of course one person can conserve, but for it to be a sustainable activity it needs to be done by many people. So thinking through again how the games went — in the end, farmers were paid on how many points they’d earned.

C: In real money?

A: In real money. That was one of the fun parts about explaining the games. Communities were invited to work on the field experiments with us, and we would let them know they were being paid for the day. And that was when you’d see that we’d piqued their interest. The payment was based on a fair day’s wage for them, making it worth their time. But the other reason was to help them think economically — if we actually pay them, and they get paid based on how many points they earn, there’s an incentive to play in a way that they’re trying to ‘win’.

We played different versions of this game, and we were trying to understanding if we gave farmers certain kinds of rewards, would they be more or less likely to conserve. The two sets of rewards that we alternated between were egalitarian and proportional. What this means is that with egalitarian rewards, everybody got the same amount of points if they conserved. Proportional was based on how many land units you gave to conserve quinoa, which would earn you more points. So if I gave 3 units to conserve and you only set aside 1, I’d get more points than you. On top of that, we measured if they could select their own groups, would they be more likely to conserve, or if we set the groups at random. And one was based on no reward at all, as a control to see if people would play a certain way. Then we did a follow-up socio-economic survey to understand the amount of farmland farmers have, how many llamas or different kinds of animals they have, and one of the most interesting parts of the survey was if they were related to each other, how closely they live with their group members, and if they ever collaborate with them.

C: To understand the social context that they were playing in. So did the farmers understand what they were doing?

A: That’s the question for us as anthropologists. And I would say sometimes they did and sometimes not. There was a really interesting mix — sometimes you would see confusion on farmers’ faces that would then shift to determination when they realised, “oh this is how I can get points”. Others would seem confused the whole time, and say “I don’t even know what we’re doing”. And I’d work the most with them if I could. Now the way this game was set up is that the farmers were not supposed to know what their neighbours chose. At the end of the round, they would end up with points based on theirs’ and their neighbours’ choices, but they didn’t know what their neighbours were choosing.

C: Why was that the case?

A: Because we wanted to understand if they were thinking as individuals, and if we introduced a reward that would either help the group or help them, would they be more incentivised to work for themselves, or work for the group. For one of these games that we played, there was a son and a dad in one group, and the son kept asking me, “you’re sure that they can’t see my answers right?”. And I’d say, “it’s just yours, it’s your individual choice”. And so then he used that to essentially beat out his dad and his other team-mates. So what we can think about here is how people chose, whether they wanted to just win money by getting points, or work together in a group. It does help us ask questions and think about why people choose to act individually or collectively in the name of conservation.

C: Why don’t you tell me a little bit about the process behind the games?

A: This was the third iteration that Bioversity has done, so it’s a sort of mix of inheritance as well as forging a new path. If this is going to be a trilogy of games, what do you want to know running for the third time, and how are you going to accomplish that in ways that haven’t been done before. There was a process of two months working with an intern. We inherited the documents of the previous games — the rule sheets, the game sheets etc, and we really thought through the language. How these games would be explained. Because the instruction sheet was something that we would read to the farmers during the games. It was kind of those tough questions of, what do we need to consider when doing this, we were working between econometric equations, data sets in terms of what we’ve seen happen before, and simply understanding the mechanisms behind these games. As I said, we’re trying to measure if an individual reward would be more attractive than a collective reward, and then how do you put numbers to that. As an anthropologist, that’s one of my questions too — how do people go from making these decisions to then put numbers and statistics behind them, and what we do with that kind of data.

C: Because that’s what people want, they want a numerical outcome.

A: Right, because it’s easy to understand and use and so in some ways, these games were about getting efficiencies in information. How do you take the complexities and details of everyday life and translate it in a way that says, “among X amount of people in my data set, conservation works better with X”? So we went back and forth thinking about what those variables would be, and we played with how many land units the farmers would have, the number of people in their groups, etc. And what other variables can we take into consideration — like weather — without complicating the game too much? That’s why it was an interesting process, going back and forth between economists, agricultural scientists, and anthropologists in terms of how do we pick the variables that are going to both give us statistically useful results, as well as being reflective enough of human choice behaviour.

This Adam Gamwell and Corinna Howland story was funded directly by readers like you.

It’s free to read because it was shared by the author. Back Adam Gamwell and Corinna Howland, and your funding directly supports their future work — You can impact the stories that get told.

Subscribe Make a One-Time Pledge

An unexpected error occurred.

How much will you pledge to support Adam Gamwell and Corinna Howland?

C: Recognisable enough to the farmers so that they know what they’re doing.

A: There’s that, too. And that was one of our biggest challenges, how to explain that. A really important question is: how does the language that we use to explain the game affect how farmers play the game? We had certain people in the team that would emphasise conservation, “do you want to keep the varieties that your grandparents had, do you want to keep this recipe that you had?”. It really instantly connected with people. And it’s a great thing to think about in terms of layers of information — how do you explain the game to farmers, but also in a way that satisfies the funding agency that gave the money for the games, that makes sure it also fits in an idiom that they would understand, in terms of bigger frameworks of conservation like the Nagoya Protocol, and games literature. So there’s a bunch of layers that don’t line up, but that have to be taken into consideration.

C: It’s interesting that you mention the funders behind the games. Could you talk a little bit more about the people that are using these games, and what they’re using them for?

A: Sure. These games are based around the idea of incentives for conservation. And this form of game is known as a public goods game. A public good is anything that anybody can use, and that my using it doesn’t affect your use of it. One of the classic examples is oxygen or air. The idea is that if anybody can use it, there’s not so much incentive to take care of it.

C: The tragedy of the commons.

A: That’s right — the idea that if everybody has access to it, that’s good, but who’s going to take care of it? And nobody does, and eventually it goes away. And this is particularly the case with market pressures. So crops fit into this idea, particularly heritage crops — your heirloom tomatoes, or traditional kinds of quinoa, or any crop that’s not hyper-commercialised. The idea of this public good game, then, is how do we incentivise people to conserve these traditional kinds that have public benefits? Because there’s no market value for them, can we displace market value being the only form that really influences people’s decision-making in what to plant? NGOs and economists use these games to measure these kinds of behaviour. What forms are most effective when design a conservation programme that uses incentives?

C: So essentially what you’re saying is that there’s a public policy application, the policy analysts want to know the biggest conservation bang they can get for their policy buck. They really need to know if the kinds of incentives they provide to people in conservation projects are going to be effective.

A: Correct, i.e. the most quinoa conserved.

C: Let’s take a little bit of an anthropological step back. Now that you’ve gone through the process of designing, running, and seeing farmers’ responses to these games, what would you say a game is?

A: Excellent question. Simply, games are a controlled way to measure human behaviour, specifically their choices. When we were thinking through designing the games, it was a question of what variables do you need to understand a certain kind of behaviour in a statistically useful way. I know this sounds strange, but think of how a skilled poker player will make choices of which cards to discard or which hands to play based on probabilities of what’s more likely to win. With these games, we pick certain variables and then think through the strategies people will use to make choices. So we’re asking the questions, why do people make the choices that they do, and how do you measure that?

C: For you as an anthropologist, why are these games ‘good to think with’?

A: For me, the question really is can we measure human behaviour by playing games? These games are based on game theory, which sounds more fun than it is. Put simply, game theory is based on mathematics, and is trying to analyse how people deal with competitive situations where their choices are also affected by their neighbours, team-mates, or opponents’ choices. Can we actually measure this kind of human behaviour?

C: I suppose it’s based on the faith that things can be measured. Which is an interesting assumption to make when you have supposedly intangible ideas like conservation. It’s a way of attempting to turning ideas and behaviours into numbers.

A: And that’s definitely something that I struggle with as an anthropologist and as we’re doing the data analysis, how do we transfer people’s determination, confusion, desire for points, trying to work the best with their group into a number, and those four things don’t show up as numbers necessarily. The person’s desire to win isn’t readily apparent if you just translate it statistically to how many times they conserved. So it’s such an interesting thing to think with, because even the idea of these games themselves are based on a model of human behaviour, the economics model of the rational human being that’s well-informed. You can say “10 people conserved and 20 people didn’t, so we have 33% conserving” but that doesn’t tell you if they’re rational or irrational, if they’re well-informed or not about the process, if they just wanted to win the game, if they wanted to get out of there. And this is one of the reasons I’m really interested in these games, to see how we can take the observations we make about human behaviour and local cultural contexts and rationalities into account. If we’re going to make numbers that’s fine, but then what happens if we also keep the anthropological story of how people did it, what their day was like, who their neighbours were. This helps us to make more sense of the games.

C: Well that was something that was interesting on the day that you came to our village.

A: Yes, I was lucky enough to have you join me. So what were some of your insights in the games we got to play?

C: I was in an interesting position, because I’d gone through the practice round with you and so had an idea of what the games were for, and the kinds of strategies for playing them. And we were with the quinoa cooperative that I work with. So I sat quietly at their tables watching them as they worked out their strategies for playing the games, and what happened is that people were nudging me saying “how can I get the most money out of this?”. But what was really interesting is that there was a group sanction placed on individuals trying to strike out and make the most money they possibly could on their own — that was the largest reward people could gain, free-riding on the backs of others who were conserving while they “sold” all their quinoa to the market. Everyone said, “no, we can’t be having that, I don’t want him to be making more money than me”. And it was kind of an egalitarian strategy in the sense that they wanted each member of the group to get the same, not necessarily because they altruistically wanted others to do well, but because they didn’t want other people to do better than they’d done. Which is quite a common cultural logic here.

A: And this is why anthropology is an important tool, if not a fundamental part of these other forms of thinking. Because we can bring in our knowledge of community logics, and the question is how do you apply this to policy thinking, if you’re going to. Because if the question is to make the most effective conservation policy or incentive mechanism then we’ll need to take into account these logics that are there, i.e. we don’t want others to get more than us. And it does also play into the idea that conservation is seen as a group activity by NGOs and policy-makers.

C: So your anthropological lens brings out this complexity, both at the level at which the games are played, and also the kinds of assumptions people make in setting up these games, and the kind of outcomes they want.

A: Absolutely. Because the games are designed to measure conservation and on one level are skewed toward helping conservation. And while that’s no dig on the games themselves, it is a great anthropological point to think about the language that’s used, the interactions between we who’ve put them together and how they’re played, and also the later question of what will happen with the data when it is set free into the wide world of policy.

C: Any last thoughts or insights that you want to give us on the games?

A: Just to reiterate, can we really model human behaviour, and can we model future action in this regard? To which I don’t have an answer, it’s a question I want to leave our readers with.